In the 1980s, I spent many of my childhood summers up in the small farm towns of the Wasatch Back: Heber, Midway and Kamas. I recently returned to Utah. The growth up on the other side of the mountain has been one of the most startling changes I’ve seen. Amid all this growth, Dendric Estate is a startup cider-making operation set amidst acres of their own apple orchards—no juice boxes here, but high-quality European-style fermented cider.

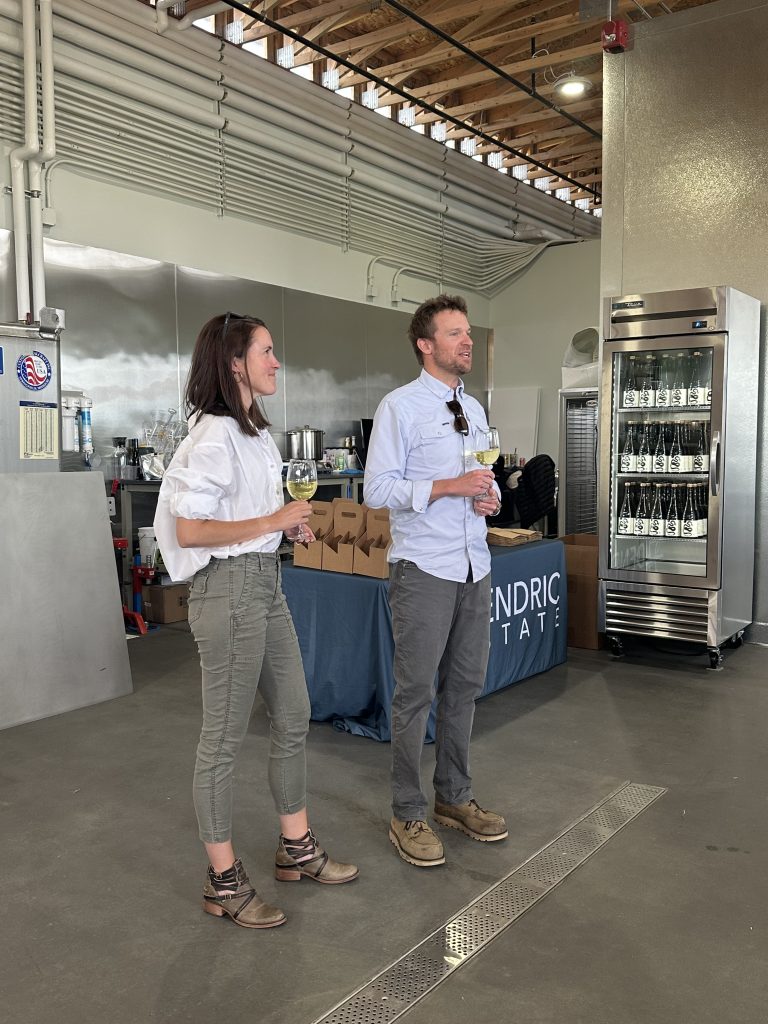

I have a hard time imagining a place like Dendric Estate in my misty memories of the Kamas valley, but it fits right into the community as it is today. Owners Brendan and Carly Coyle certainly understand what the future holds in Summit County. Brendan spent years at Park City’s groundbreaking High West Distillery, helping to grow Utah’s burgeoning culture of spirit makers. Brendan and Carly wanted the challenge of building something new from the ground up, or in this case, from the dirt. In 2019, they bought a 20-acre dirt plot just north of town on the long alluvial slope dropping down from the flank of the Uintahs to the Weber River far below. At 6,440 feet, they decided to make wine from apples.

Apple trees have grown in Utah since the pioneer era. Many of those historical varieties were crabapples—small, tart, and hardy survivors that thrived in the short growing season at altitude. Unlike the big, watery, sweet varieties common to American grocery stores, crabapples make a great base for baking, cooking and distilling into cider. It’s easy enough to add sugar, but starting with a tart, firm, complex flavor profile is a must to make the kind of crisp, dry, in-your-nose cider that you usually find in the spiritual home of cider-making, Normandy.

That’s exactly what Dendric Estate has created with their first product, which they have appropriately named Dry Cut. This bubbly, punchy drink has more in common with a good champagne than with the sweet alcoholic apple juice that InBev will sell you in a can.

It took five years of hard work to get to this stage. The first thing the Coyles did during the pandemic was plant trees—36 different apple varieties, to test how they grew in the Kamas soil and climate. Then they built a production facility, one piece of machinery at a time. They use the Charmat method, the same secondary fermentation process that’s used for sparkling wine, and their spotless building is filled with a giant, bright and shiny fermentation tank for the secondary fermentation that they use to give their cider that champagne life.

Of course, apple trees take years to grow, so Dry Cut is sourced from apples further up the Great Basin, mostly in Idaho. The Coyles will be harvesting their own fruit for their 2026 product, as well as sourcing from other Utah farms, to bring their cider even closer to home. More importantly, they have narrowed in on successful varieties that they want to grow in bulk, and 3,200 new trees have been ordered for planting, including Redfield, a variety whose flesh is red as well as its skin. It will make a cider with the color of rosé.

As far as making cider in the conservative Kamas Valley goes, the Coyle’s have had a positive response from their neighbors.

“There are some multi-generational Mormon families that aren’t fans of alcohol,” Brendan admits. “But here’s what we come to connect—the Kamas Valley historically has been a land of ranching and agriculture. But we’re only 20 minutes from Park City—We’re so close that we’re experiencing land prices that are equivalent to certain areas in Park City. What we all agree on, and where we get a pat on the back from the locals that grew up here, is that we’re doing agriculture differently. It might not be the way that they would do it historically, but we’re promoting and protecting and growing agriculture, and we’re doing it in a way that can compete with Park City land prices. It’s tough for traditional agriculture to compete with that. What we wanted to do was bring a new type of agriculture to the valley that can compete, but can also preserve the heritage. We’ve committed to 75% of our 20-acre estate to be pure agriculture.”

The Coyles are also committed to building a sustainable business—they’ve applied for the permitting that will allow them to recycle their wastewater for reuse. Using organic farming methods, they’re avoiding the pesticide-heavy practices of much fruit farming.

You may not be able to taste all this toil and labor in the glass, but what you do taste—a clean, fresh, bubbly, delicious cider wine—is proof of their concept. The Wasatch Back could be America’s next great cider country, and if it is, a generation from now, the Coyle’s will be remembered as pioneers, breaking the tough soil and making a new way of life in the high mountains.

See more stories like this and all of our Food and Drink coverage. And while you’re here, why not subscribe and get six annual issues of Salt Lake magazine’s curated guide to the best life in Utah?